Despite the huge numbers of laws (the books containing them take up a library), too many in Congress have long thought it was too difficult to control us and sought to find another way. The original idea behind the Commerce Clause was to figure out how to deal with cross-state issues; early on, the 13 states operated pretty much on their own. This particularly affected debtors, of which there were many, and what they owed someone in another state. Congress initially thought they would help relieve debtors, since those they owed were fewer in number.

In 1787, a convention convened to discuss issues with contracts that affected commerce. The Commerce Clause itself (Article I, section 10) barred states from interfering with contract obligations. The clause itself gives Congress the power "to regulate Commerce with foreign Nations, and among the several States, and with the Indian Tribes." This began a “free trade zone” among the states, as well as to move the ability to negotiate international trade to the President, instead of the several states. This was finally enacted on January 1, 1808.

However, the clause did not define what constitutes “commerce,” nor did it explain what it meant to regulate it. In addition, “among the several states” wasn’t precisely clear. It is the problem with these issues that have led to massive abuse of the clause, which impacts us today.

Wickard v. Filburn

In 1941, an Ohio farmer named Roscoe Filburn was charged with violating federal low by growing too much wheat. He grew 23 acres of winter wheat which was 12 more than he was allotted under the Agricultural Adjustment

Act of 1938. He was charged $.49 per bushel which meant $117.11 for the additional 239 bushels (around $2500 today). He refused to pay, arguing that this law was unconstitutional especially as the additional wheat was only used by his family and livestock. Thus, his “extra” wheat never entered “commerce,” interstate or not.

He lost. SCOTUS decided that if an activity exert a substantial economic effect on interstate commerce, they could regulate it. Basically, they claimed that as Filburn was using his own crop, he wasn’t buying it from anyone else or across state lines. Is this substantial? Really? Imagine – how impactful was that? But this was one of the beginnings of Congressional overreach. Some of it started years earlier with the drug trade which is far more complex. I’m not covering it here.

It Gets Worse

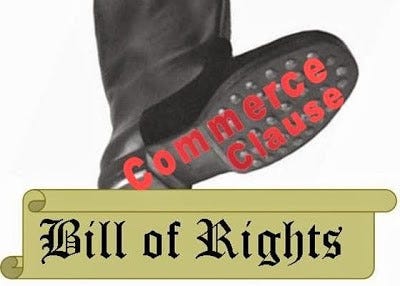

Over several more cases, the Commerce Clause was viewed by Congress to allow it to do pretty much anything they wanted to do; a useful excuse to behave in a way it was never intended to be able to do.

Federal Gun Control

As with all governments trying to exceed the limits on their power as imposed by the people and/or the Constitution, Congress wanted to regulate guns. It’s all very well to have people protecting Congress, cut they didn’t want “the people” to have them. People with weapons could protest against their own government. They didn’t want that. In 1934, the National Firearms Act was enacted in the Internal Revenue Code. It was mostly seen as a way to raise government funding, requiring registration and tax with criminal penalties for failure to comply. This was a similar step to what they did to regulate drugs. It’s always easier to use the IRS to get to people. They were particularly focused on what they considered “dangerous: “machine guns, short-barreled rifles and shotguns, along with silencers.” It was pitched as a revenue measure, not as a crime-control act, though we know better, don’t we?

While discussing the bill, they focused on scary people like Dillinger. Attorney General Homer S. Cummings said, “If we make a statue absolutely forbidding any human being to have a machine gun, you might say there is a constitutional issue involved. But when you say instead that the absence of a license showing payment of the tax has been made, you can call that a crime.” Four years later, Congress got rid of this pretense. The Federal Firearms Act of 1938 explicitly tried to regulate commerce in guns and imposed a requirement for manufacturers, importers and dealers to be licensed. Expanded in 1961, they added prohibitions not just to those convicted of violent crimes, but also to reduce access to guns by people who committed non-violent crimes where the penalty was greater than a year.

At first, the gun had to be obtained across states lines at some level or other, but in 1986, any possession would be covered by these firearm laws, regardless of whether it ever crossed state lines. This is critical. You should not be able to expand the Commerce Clause to cover anything you want it to. Except, that you can, if the people aren’t watching.

United States v. Lopez - 1995

The case involved the challenge to the Gun-Free School Zones Act of 1990, which made it a felony to have a gun within 1000 feet of a school. SCOTUS judge, William Rehnquist wrote, “The Act neither regulates a commercial activity nor contains a requirement that the possession be connected in any way to interstate commerce.”

Congress pretty much ignored this and amended the law with scare tactics, ignoring the plain fact that this is NOT commerce. Sadly, courts of appeal felt that the small changes Congress made to the law to get past SCOTUS made it okay. Now, they are wont to claim that nearly everything “affects interstate commerce,” to get around pesky Constitutional limits. Originally using taxing powers to control things it had no right to do, Congress has now found it possible to control us with the Commerce Clause in ways that make no logical sense.

Be prepared for what they want to do next. There appear to be no limits on their power now.

And once the right or “privilege” is gone, good luck getting it back.