In 1968, Johnson signed into law the first federal hate crime legislation making it a crime to “use or threaten to use force to interfere with any person because of race, color, religion or national origin.” In 2009, the Shepard Byrd Act added the concepts of perceived race, as well as gender, sexual orientation, gender identity or disability to the concept. States rapidly adopted these creeds to make it a more serious offense to do such things as lynching another person. States jumped on the bandwagon, as the crimes that inspired the laws were truly gut-wrenching.

Over time, the laws evolved, at least in the way they were administered. First, it became a hate crime if the parties involved differed in a key characteristic, such as white on black, straight versus gay, etc. No attempt was made to prove that the crime involved actual hate. It was enough that the crime appeared to have targeted someone different from ourselves, regardless of the kind of crime involved. The enhancements soothed the public’s desire for “fairness.” But is it fair?

Another factor is the desire to look for “hate” even when it may not be there. Though none of us can know, an alternative theory of the George Floyd case is that they knew each other from Chauvin’s outside job at the same bar Floyd worked at. If Chauvin had been involved in illegal activities as part of that job, and Floyd knew (but didn’t know Chauvin was a cop), Chauvin might have reasoned that Floyd needed to go so he couldn’t “out” him. The other theory makes little sense. A guy is arrested for a petty crime and Chauvin goes ballistic and ensures he dies because he’s black. That kind of racial hatred would have shown up long before the incident.

Is a black person more seriously hurt by being murdered because the person who killed him is white? I think most people would agree that dead is dead.

Begun as a way to protect truly marginalized people, it’s now a heavy stick to wield over anyone who happens to choose as their victim someone unlike themselves. Are you any less dead because the person who kills you is the same race as you? Yes, there are still some very obvious “hate” crimes, but they are in the minority. But prosecutors look for reasons to add hate to the menu of charges, perhaps in response to public demand but in part to heighten their profile as they pursue the charges.

Do we really need these enhanced penalties? Don’t the laws cover these crimes adequately? Aren’t the penalties for crimes strict enough? Is race, religion or sexual preference the driving concern? In some cases, it probably is, but even so, why make the penalties worse? According to liberal experts, punishment doesn’t work. If that’s true, then increased penalties for certain kinds of crime don’t make any sense at all. More important, does this even make a difference? Hate crimes appear to be on the rise, but that may simply be the choice of how they are prosecuted.

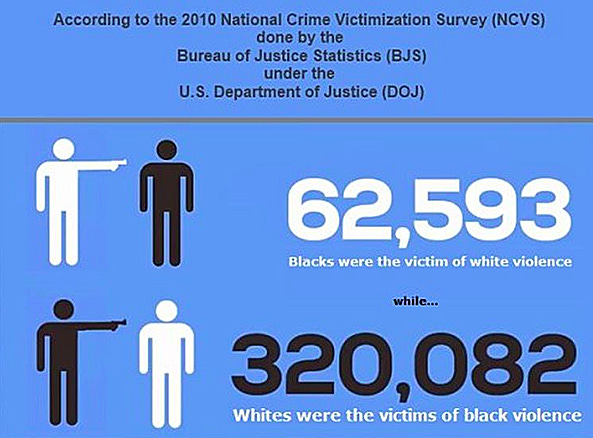

Hate crime prosecutions product a great deal of publicity, so it’s easy to think they are more common than they are. But if you look at statistics for murder, the numbers that are actually dubbed “hate” are much smaller than the total murder rate. Doesn’t that tell you something? Murder isn’t going away. Culling some of them out and call them hate crimes doesn’t solve anything. Let’s do away with these laws and look to find better ways to actually address crime (not motive).