How Did it Come About?

Theodore Roosevelt signed the Pure Food and Drug Act in 1906 which was designed to help protect the nation from adulterated, damage, low-quality products. It wasn’t until 1927 that the FDA was founded to carry on the work.

What’s Wrong with It?

The FDA’s biggest claim to fame came in 1960 when, under a lot of pharmaceutical pressure and desire from pregnant women, the drug, thalidomide, was not approved for sale in the US because the FDA had concerns about it. This turned out to be a good decision. Many American women who imported thalidomide from Europe delivered

deformed babies. The drug wasn’t safe for pregnant women.

The FDA have ended up pulling various drugs that have caused issues that weren’t revealed in testing. This all sounds really good. But the problem is…how many drugs never made it to market that could have saved lives?

Right now, the agency has a budget of $6BB and a staff of 18,000. But that doesn’t count the cost of time-to-market for important drugs. The bureaucracy imposed by the FDA means that the patent life for drugs has shrunk from 20 years often to less than 10. It is very costly to find a potential new drug to develop, because most ideas in the lab come to naught. Delays in the approval of new drugs cost lives. The huge investment in time and associated costs to get a drug approved by the FDA limits the ability of each company to invest in drugs. Companies can’t always recover their costs in a reasonable period of time. How do I know this? For a number of years, my father was the Director of Scientific Liaison for Cutter Labs, which meant he worked directly with the FDA to try to move drug approval along for his company. I heard the stories of the costs and delays.

It's easy to say that a given pill couldn’t cost much to manufacture, which is why people push hard to get prices down. But when you factor in all the years of false-starts and drugs that sound good but aren’t effective enough, and the long time to market when one is finally found to actually works, the actual cost per pill is often much higher than any of us could believe.

Oddly, Aduhelm was quickly approved by the FDA under a special “accelerated approval process,” even though it has been shown to be expensive and not all that helpful to Alzheimer patients.

Covid Mistakes

The FDA stopped researchers from using their own tests to get a handle on early Covid infections in 2020, requiring that the only usable tests were those from the CDC, (and those tests weren’t that good, took too long and weren’t generally available.) The faster you get on top of the disease, the more likely you can develop treatments and save lives. The AstraZeneca vaccine was available in other nations, but the FDA wouldn’t approve it. It’s still not clear why.

A more pressing problem is the use of EUA (emergency use authorizations), to rush Covid vaccine to market. Surprisingly, there was almost a complete lack of urgency to push for treatments, given that (a). many people were already sick and (b). vaccines usually take a long time to develop. There is a panel that is supposed to collect adverse reactions to a drug/vaccine. However, they haven’t collected much of the data and certainly haven’t made it widely available, which means that more kids are having heart problems from the vaccine. And that’s only one of the reactions people have had. We want to be treated, not just forced to rely on vaccines that don’t prevent Covid and come with side effects.

*** But you can’t get the cheap and effective treatments for Covid. Despite much data on the value of vitamin D-3 to boost your immune system, and the efficacy of ivermectin, fluvoxamine and hydroxychloroquine, it is almost impossible to see the data on D-3 or to obtain the other drugs. I know ivermectin works – my husband and I used it to shorten our latest Covid infection. And yes, we are 4x vaccinated.

Right To Try

If you’re dying and there is nothing else doctors can do for you, wouldn’t most of us be willing to take something that isn’t fully approved by the FDA? The Goldwater Institute began pushing the concept of “right to try” with the following rules, which have been accepted in the Trump-signed act with little pushback from cancer institutes and leading doctors.

Anyone with a terminal illness is eligible for right-to-try.

Any drug that’s passed phase I trials, has an investigational new drug (IND) application, and is still under clinical trials is eligible for right-to-try.

There is no liability for doctors or companies participating in right-to-try.

Insurance doesn’t have to pay for right-to-try drugs. (As I’ve discussed on a number of occasions, this provision can also be reasonably interpreted as saying that insurance companies also don’t have to pay for the treatment of complications that might occur as a result of the use of a right-to-try drugs.)

Patients wanting right-to-try drugs are on their own when it comes to cost. (A few states—for example, Texas—forbid companies charging for right-to-try drugs.)

Drug companies don’t have to provide their experimental drug under right-to-try if they do not wish to. It is this provision that has led some critics to note that “right-to-try” is really more like “right-to-ask,” given that drug companies are under no obligation to provide their experimental drugs to anyone, paid or unpaid.

Sounds good to me. But the FDA and other governmental agencies have approved very few right-to-try cases, no matter how dire the situation. It’s true that many drugs won’t actually work, but remember: people in these situations have been known to go to shady doctors in other countries trying crazy treatments. This is a better option for them.

The other side of things is that doctors often prescribe “off-label” which simply means that the drug was approved by the FDA for one ailment but they use it for another, given that the doctor has seen evidence that it works. Those Covid drugs I mentioned are a clear example of this. The few and late-to-market drugs that the FDA says can be used for Covid are very expensive and don’t have a great track record in healing people.

Growing the Agency

More recently, the FDA has jumped into areas it was never supposed to handle, further adding to regulations, delays and costs. Gun control is not their job. There is a laundry list of other areas of abuse. I won’t go into it here.

What Should We Do?

Most of us are unfamiliar with Underwriters Laboratory (UL), but if you look at virtually any electronic appliance, the letters “UL” will be found somewhere on it. This private entity charges manufacturers to test and certify the safety of electronic products, making it unnecessary for us to stress that plugging in that new TV will electrocute us. Given how inexpensive so many of these devices are, it is clear it doesn’t cost that much to do the testing. Still, companies could produce products without going thru that verification process.

Privatizing the FDA and making it into something more like this would allow a better and more efficient approach to approving drugs. Yes, it would cost a lot more than certification of electronics, but as a business, it would be done efficiently and effectively. Governmental agencies always grow, add rules and regulations and become less efficient and more troublesome over time. End the FDA and get the government out of the business of drug approval.

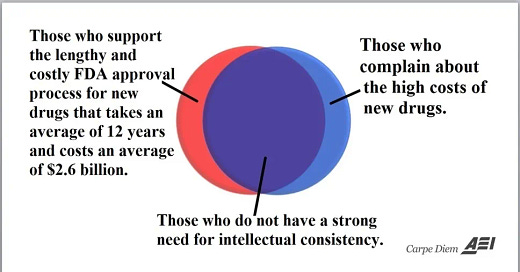

This diagram explains the problem. Too many people support the FDA’s process, but then feel that drug prices are too high. You can’t have cheap drugs and the FDA. It simply doesn’t work.

I get that testing a drug adequately can take years. The right-to-try scenario you mentioned is a good idea and I would think help the testing timeframe as well. It’s a tough call no doubt.